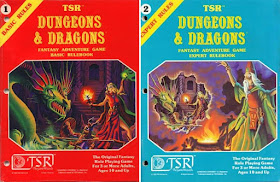

America is having a moment. We're emerging from weeks of protests in the streets regarding matters of race and equality after the public murder of George Floyd. Many corporations are taking a stance on how their products or services will change to reflect new attitudes. Brands are dropping outdated imagery, making donations in show of support, or publicly affirming their positions on diversity and inclusion. The NFL made a statement recognizing they need to support their black players. Even the publisher of D&D came out with their own statement on diversity in Dungeons & Dragons, as the shifts happening in the larger culture will be reflected in the game, too.

|

| No limits: Elf dentists, Orc wizards. |

Historically, the game has had a strange relationship with the concept of race. In the versions I learned in the 1980's, elves and dwarves and halflings were "demi-humans", and all the "monster" races were humanoids. It was implied humanoids were "born bad" and had fixed alignments in their monster stat blocks. After 40+ years of gaming, player preferences have shifted away from the underlying source literatures. There are game worlds where the halflings have been re-imagined as horrible little cannibals, and others where goblins are a mischievous player character race. Orcs are popular in video games and also as a playable race in some D&D game worlds. With the new Wizards of the Coast position, all character race options are now defined as "humanoids"; they can be any alignment, and players will have some flexibility on ability score increases and cultural backgrounds. Time for an orc wizard? These changes seem fairly benign, but there are interesting implications for world building.

Here's a thought experiment - consider a human-centric game setting, something like Game of Thrones, with your faux Viking culture (Ironborn) and your faux Mongols (Doth Raki) and your horrible western knights. There was no dearth of conflict, drama, bloodshed, or violence, to support a rich fantasy campaign world in GRR's setting. You can create interesting villainous cultures and also have sympathetic characters and engaging stories involving members of those cultures*. Where there is irrational antipathy and prejudice - for instance, the way the Westerosi and Night's Watch view the Wildlings from beyond the wall - we (the readers and viewers) are given a broader view and see the Wildlings as a multi-dimensional and admirable group of people. (I'd be on Team Tormund Giantsbane, that guy is legendary.)

To the extent future game worlds will begin to put the various humanoids on the same footing as humanity, I can see myself drawing on sources like Westeros for inspiration on both presenting adversarial cultures, yet having sympathetic members of those cultures. I like making elves into the awful ones in my games, they're ripe to be cast as haughty villains, and let the player characters be the exception if they pick an elf. I'm looking forward to developing an orc culture on one of the continents and casting their values in orcish terms - they embrace pragmatism and common sense - a smart orc looks after themself! If a player wants to be an emigrant from one of the humanoid cultures in the broader world, it'll be great fun. Games are more interesting when there are grey areas around allegiances and alliances, and the players need to make choices about parleying with opponents instead of attacking everything on sight. Dust off those reaction rolls and morale checks for a change (or add useful ones to your 5E game... they're a bit lackluster in the 5th). For humanoid-style monsters that you want to keep as "kill on sight" I'd suggest changing their designation from humanoid to something more alien or monstrous. Gnolls, for instance, are supposedly descended from hyenas who ate demon-tainted corpses and mutated into bi-pedal ravagers; since they're practically demon spawn already, let's just tag them as "fiends". I think one of the designers already mentioned this might be in the offing. In one of my settings, goblins, hobgoblins, and bugbears will be recast as evil fey, servants of the Winter Court, who sneak into the world to cause mischief, collecting infants for David Bowie.

I didn't see much commentary on the blogs about the WOTC announcement or its implications. The again, I don't know many 5E blogs, and there's not much reason for OSR gamers to pay attention to the mothership. For me. there are some intensely personal reasons to be sensitive to race depictions in game worlds. My youngest son is adopted, a proud African American 13 year old kiddo, and it's been a journey to learn to see the world through his eyes. (I'm certainly not there yet). He relates to Black Panther, Nick Fury, Luke Cage, and the Falcon a whole lot more than Aragorn, Gandalf, Legolas, or anyone else from Tolkien's bunch. Part of our "Living Covida Loca" has been family movie nights where we've watched Lord of the Rings, all the Marvel Universe movies, and now working our way through Star Wars saga, so we've talked about which characters he likes quite a bit. The phrase I've heard online is "representation matters" - people want to be able to see themselves in their entertainment media. That could mean human characters that look like them, or humanoids that are more relatable than bleached European elves. I support this new approach by Wizards of the Coast, and plan to work these ideas into upcoming settings.

*I'm aware Westeros is not entirely without problematic depictions, particularly where the Mother of Dragons is concerned.